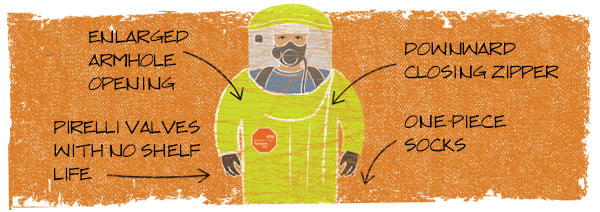

Tychem® 10000—Garment Enhancements Made for You

By Dan Bowen

Technical Specialist, DuPont Protection Solutions

If you’ve used Tychem® 10000 Level A suits in the past and recently ordered new ones, you may have noticed some changes. DuPont uses voice of customer input to both develop new products and improve/enhance existing garments. Recent customer feedback has led DuPont to make a number of significant design improvements to Tychem® 10000 suits, which are listed below.

On front-entry Tychem® 10000 suits:

- The zipper path has been straightened to reduce likelihood of pinching the zipper sealing during closure or opening.

On all Tychem® 10000 suits:

- The zipper direction has been standardized to close downward and open upward. Closing downward allows the donning partner to check that the zipper is closed without the use of a step stool.

- Originally, zipper flaps included a horizontal top flap. The new downward-closing zippers eliminate the need for the top flap. The result is a permanently sealed double-zipper covering flap.

- The armhole opening has been enlarged to make it easier for wearers to remove their hands from their gloves and sleeves and check the gauges and systems inside their suits.

- The fit and feel of the sock has been improved with a “tube sock-like” one-piece sock replacing the “heeled sock” design of the original suit.

- The boot covering flap has been lengthened to accommodate taller hazmat boots (previously, users often needed to shorten their boots by cutting them).

- The knee patch has been eliminated because the longer boot flap forms a knee reinforcement when kneeling.

- The elastic in the lower boot flap has been eliminated because the fabric now falls to the bottom of the boot naturally. (This also eliminates the former risk of needle punctures through the material where the elastic was attached.)

- The boot flap has been shortened to fit the boot better. (Previously, the fabric extended below the top of the lower boot, bending the boot flap.)

- All suits (Tychem® 10000, Tychem® 9000, Tychem® 10000 FR, Tychem® CSM) now have Pirelli valves with no shelf-life limits.

- Exhaust valve covers have been redesigned to eliminate snaps and multilayer closure requirements.

- Exhaust valves have been relocated to accommodate visor and zipper redesign and are located with consideration of SCBA air system design.

- Size XS has been added, expanding the size offerings from XS to 6X.

Par for the Course

By The Glow Worm Editors

If you see "glow worms" playing miniature golf, you’re probably not hallucinating. It could be a few local hazmat first responders honing their dexterity skills.

Just ask John L. Filer, chief of the Charles County Department of Emergency Services’ EMS Division in La Plata, MD. John’s tactical response team consists of 30 individuals from different disciplines, including fire service, public works and law enforcement.

Roughly once per year, team members train in Level A suits. According to Filer, “we play mini-golf and other games while fully suited, because it builds dexterity and overall confidence in how the suit feels and how you can move in it.”

Filer says that building this kind of confidence while in a relaxed state better prepares wearers for the high-stress, real-world scenarios in which they will later don the suit. Charles County EMS personnel have also played kickball in Level A suits, and Filer says they’ll be playing Frisbee golf in the near future.

What unusual hazmat training practices have you seen?

Share your experience with DuPont and your story could be featured in the next issue of The Glow Worm.

Hazmat Through History: Biohazard Symbol

By Daniel Hammel

Garments Inside Sales Manager, DuPont Protection Solutions

Prior to the mid-1960s, laboratories across the United States used a variety of symbols to identify biohazards. The Army used inverted blue triangles, the Navy opted for pink rectangles, and the Universal Postal Convention required the use of a white interlocking staff and snake against a purple background. A universally recognized symbol proved elusive.

In 1966, Charles Baldwin of the Dow Chemical Company was working with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) on containment systems when he noticed the wide array of symbols that were being used to denote biohazards. Baldwin worked with Dow’s marketing team to develop a symbol that could serve as a universal warning.

Baldwin’s team designed more than 40 symbols, which were then evaluated by test groups across the country. The new symbol was tested against several criteria: striking in form; unique and unambiguous; recognizable and memorable; easily stenciled; symmetrical; and acceptable to people from various ethnic backgrounds. The symbol also needed to be previously meaningless; that is, Baldwin wanted to educate people on what the new symbol meant, rather than elicit any unintended associations.

The symbol they finally chose scored best for memorability and was determined unlikely to evoke other meanings. It was blaze orange, a color that had been identified during Arctic explorations as the most visible in the greatest range of conditions. The finished symbol’s symmetry allowed it to be recognizable regardless of how it was positioned.

The next year, Baldwin presented the symbol to the scientific community as the new standard. Eventually, the NIH, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) adopted the symbol, which prompted its standardization across the United States and in many places around the world.

To find out which DuPont products offer suitable protection from biohazards, visit www.SafeSPEC.DuPont.com.

What to Do When Facing Multiple Hazards

By Susan Lovasic

Global Regulatory Affairs Manager, Tyvek® Protective Apparel

Wouldn’t it be nice if all hazmat threats were one dimensional? Unfortunately, real-world response situations are often much more complicated. A good example is the scenario of a toxic or corrosive chemical release that is accompanied by the risk of flash fire. You may encounter dual hazards like these with just one chemical or they may arise because of other chemicals nearby.

Whatever the reasons behind dual hazards, you must protect yourself from them. The good news is that National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) standards already exist that provide testing and certification against chemical and flash-fire hazards for personal protective equipment (PPE). Both NFPA 1991 (Level A gas-tight suits) and NFPA 1992 (Level B liquid-tight suits) offer an Optional Flash Fire Escape certification. Additionally, NFPA 2112, which certifies suits to offer flash-fire protection performance, can be coupled with other NFPA chemical PPE standards (like NFPA 1992) to provide protection from dual chemical and fire hazards.

Check your existing PPE. Is it certified for possible chemical and flash fire exposure? Having the right PPE available before you arrive at the response scene can give you the peace of mind you need to tackle the challenges of the non-ideal hazmat world.

Resource library

Find technical information, videos, webinars and case studies about DuPont PPE here.