Building the plane as we fly it: Lithium-ion batteries in practice

By Bobby Salvesen and Mike Monaco

The Haz Mat Guys Podcast

With the world seemingly being consumed with the latest calamity, there is much discussion on who is ultimately responsible for it, whether this is a fire or a hazmat incident, and what we wear. As the frequency and the sharing of information becomes more prolific, the firming of operational guidelines and techniques will inevitably happen. For now, we would like to take more of a “consider this” approach to personal protective garments for battery response. Due to the infancy of the topic, the standards and regulations are behind. Through thorough discussion, we can form the standard and put forth a best practice for handling this type of event.

Currently, we would make the wager that a vast majority, if not all, battery responses use turnout gear to handle this emergency. This makes sense since the primary hazards are heat and fire. However, upon further inspection, heat and fire are not the only hazards here. Of course, there are incredibly hazardous gases that are emitted. We don our SCBAs and just about all respiratory hazards are mitigated. Now we can dismiss that for the time being and focus on what we wear to protect our bodies.

But turnout gear has its pros and cons as well. It is bulky; difficult to work in when working in tight spaces like cell phone vaults and energy storage containers; and, depending on the month, can be hot and heavy. Turnout gear protects from heat, but it’s questionable if this protection extends to a battery’s heat. Since a battery’s heat is typically produced in a small, focused location at about 1500°F, turnout gear may not offer even limited-time exposure. As for the possibility of electrical arc flash, turnout gear can give some “distance” from the contact point to the skin, but how much is anyone's guess. Wearers are also indirectly protected from vapors and solids to a limited degree.

If we consider the electrical component, as done in the electric generation industry, NFPA 70E Cat 2 flame-resistant garments may be regarded as something to investigate in the future. For example, if the garment could be paired with an additional CR/FR layer over that, it may be an economical option for some departments or those doing a tremendous number of battery responses.

Most responders will say that the turnout gear works fine. And it does…for now. The industry makes new garments to handle things all the time, from garments with improved design features to garments that offer multi-hazard protection. Suppose this battery trend keeps going the way it is. In that case, a conversation needs to begin in your mind, spill onto the kitchen table at work and become a national (if not global) discussion around the most efficient thing needed to respond to this type of emergency.

The argument can be made that “this too shall pass.” It will. Technology is improving, and the military is already six versions past what we see in the streets today. But this is something we are dealing with today, so let’s start the conversation.

As you can imagine, this topic is constantly evolving. It’s something we try to address frequently on our podcast, which you can find on our website: thehazmatguys.com. Take a listen or reach out to us for training on this and many more topics.

Hazmat through history – NFPA hazard diamond

By Daniel Hammel

North America Marketing Lead – Chemical Industrial

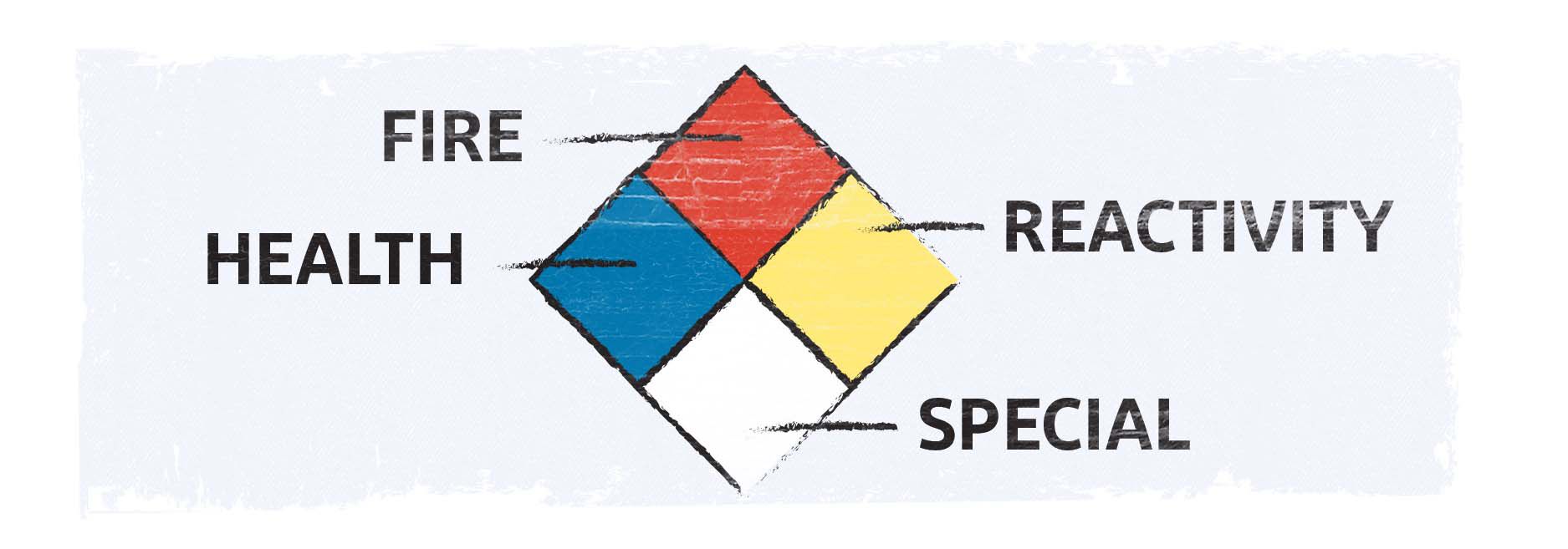

The NFPA 704 hazard diamond is seen by millions of people every day, although many of these people probably don’t know what the colors, numbers and special characters signify. But for those who need to know – and do know – the coding, the NFPA hazard diamond provides invaluable information to help keep themselves and others safe from potential hazards.

NFPA 704, first developed by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) in 1957, is the American standard for identifying hazardous materials. The goal was to protect the lives of people in various industrial or storage locations where a fire hazard was possible or imminent, and where the surrounding materials’ flammability was not immediately apparent.

Four years later, the NFPA adopted the colored diamond design that we are familiar with today, which helps first responders decipher hazards during an emergency response. The blue, red and yellow sections of the hazard diamond provide a hazard degree rating of 0 (minimal hazard) to 4 (severe hazard). The characters or symbols in the white section of the hazard diamond correlate to a specific hazard. The colored sections of the hazard diamond correspond to the following types of hazards:Modern respiratory protective equipment (RPE) is available for myriad applications and in various forms, including cartridge respirators, powered air purifying respirators (PAPRs) and self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA), to list just a few. Advancements and innovations continue to be made in the form and function, as they have for the past couple hundred years.

- Red – Fire hazards (from not flammable to highly flammable under normal conditions)

- Blue – Health hazards (from normal material to deadly material)

- Yellow – Reactivity (from stable to may detonate)

- White – Specific hazards (e.g., corrosive, oxidizer or radiation)

What happened between the development of NFPA 704 in 1957 and the adoption of the hazard diamond by NFPA in 1961 that triggered the creation of this highly informative yet simple-to-understand tool?

We can thank a creative fire marshal and an unfortunate incident in Charlotte, North Carolina, in 1959 for the hazard diamond that we see in so many places today. That summer, the Charlotte Fire Department had responded to a former site of the Charlotte Chemical Company. A large vat was burning after being left in a building that was set to be demolished. The firefighters thought the vat contained only kerosene, but in fact, the vat held a substantial amount of metallic sodium sealed in kerosene.

Additionally, heavy rain from a recent hurricane had penetrated the vat, which is what triggered the initial reaction with the metallic sodium and ignited the kerosene. Firefighters initially fought the fire as they would any kerosene fire, but as it continually grew worse, they decided to switch to foam to try to extinguish the fire. Before they could do that, the vat exploded, injuring thirteen firefighters, some severely. Had the firefighters known what was in the vat and understood its reactivity with water, this tragedy may have been avoided. While the events of that day were serious and devastating, they inspired Fire Marshal J. F. Morris to develop the system of diamonds, colors and symbols to identify hazardous materials that we are familiar with today.

To learn more about DuPont products that provide protection against chemical and flame hazards, please visit DuPont™ SafeSPEC™.

Bias for action: Team Rubicon

By Barry Bachenheimer

EdD, NREMT/FF

This is an abridged version of the original article, published in EMS World, with permission of the author.

An EF-3 tornado blows through the street of a Midwest town. A hurricane may have decimated parts of the Florida panhandle. Or maybe an unpredicted winter storm has damaged homes in an upstate suburb.

In all these cases, you will have local fire departments, EMS, police, OEM and governmental agencies on the scene quickly and for the days and weeks after to help in rescues and emergency response.

But what about after the initial emergency is over? You might get a team from FEMA as well as the Red Cross. If your area has a need, you might also get a response from Team Rubicon.

What is Team Rubicon?

Team Rubicon is a veteran-led humanitarian organization that serves global communities before, during and after disasters and crises. Their mission is “providing relief to those affected by disaster or crises, no matter when or where they strike. By pairing the skills and experiences of military veterans with first responders, medical professionals and technology solutions, Team Rubicon aims to provide the greatest service and impact possible.”

Born in 2010 after a large earthquake in Haiti, Team Rubicon was founded by a small group of United States Marine veterans whose goal was to repurpose veterans’ skills for disaster relief. Starting with a small group in 2011 in a response to a tornado in Alabama, Team Rubicon has since grown to encompass more than 150,000 personnel and has responded to over 1,100 incidents over the past thirteen years.

Team Rubicon engages in a variety of activities. In the beginning, they focused on disaster response and humanitarian aid. Today they are a multi-mission agency providing a variety of services including removing mud and muck from flooded houses, emergency medicine, incident command, cutting downed trees off of roofs, repairing damaged homes and clearing debris off roadways.

Over the past two years, the group’s mission has expanded to include vaccine distribution, assisting with COVID testing, and the formation of the Veterans Coalition for Vaccination, which focuses on building national vaccination trust in addition to other core tenets such as fighting the spread of vaccine misinformation and equitable distribution of vaccinations to underserved communities.

Why veterans?

For some members in the service, the transition from military to civilian life is not the easiest. According to Team Rubicon’s website, “Continued service through disaster response provides the elements of purpose, community and identity that are often difficult to find after taking off the uniform. These intangibles are extremely helpful in creating a successful transition from military to civilian life.” Veteran volunteers work alongside first responders and civilians to form a strong force multiplier to assist local agencies. Volunteers for Team Rubicon are affectionately known as “greyshirts.”

“All about the connections”

William Porter is director of the Operation Support Branch for Team Rubicon. The former Air Force veteran and law enforcement officer discovered that he could use many of his skills acquired in the military for disaster response.

Porter started volunteering with Team Rubicon in 2012 and has worked his way up to his current role. “It is all about the connections,” shared Porter. “The success of the group is about connections with groups like FEMA; maintaining good domestic and international relations; and working with our government, corporate and NGO partners.”

Partnering with DuPont

Recently, Team Rubicon and DuPont announced an expanded partnership. DuPont has been assisting Team Rubicon with donations of Tyvek® suits for the last several years. Tyvek® suits are worn for a variety of missions, from cleaning muck out of flooded homes to assisting at COVID vaccination sites.

“As a premier manufacturer of protective gear, their name is well-known and they are the science and safety experts,” shared Porter. In addition to providing personal protective gear that keeps Team Rubicon volunteers and personnel safe, DuPont is now providing even more resources, including subject matter experts in disaster response, training resources and ad hoc safety officers for incidents. “The sky is the limit when it comes to this partnership,” said Porter. “They even help with town hall meetings in affected towns to help folks get back to their homes after a disaster.”

EMS connections

According to Porter, like EMS, “Team Rubicon is always preparing for the next response.” Team Rubicon was the first North American NGO to be internationally verified by the World Health Organization as an Emergency Medical Team Type 1 (mobile) unit.

Team Rubicon is always recruiting new volunteers, both veterans and non-veterans alike. “EMS folks would make amazing volunteers for Team Rubicon,” shared Porter. “If you have a bias for action and you want to put your footprints on the world while you help others, Team Rubicon has a spot for you. In EMS, sometimes you get a thank-you and sometimes you don’t. Either way, you often don’t find out what happens after you deliver your patient to the hospital. In disaster relief with Team Rubicon, not only do you get the satisfaction of helping people, you are helping folks navigate their recovery for the long term after a major incident. The look of gratitude and relief people give you makes it all worth it.”

For more information about Team Rubicon, including information on how to volunteer, check out teamrubiconusa.org/volunteer/.

Read the full article on EMS World here.

Hazmat on the go – Transportation regulations: Flammable and combustible liquids

By Kathryn Novelli

Senior Marketing Analyst

Handling and transporting hazardous materials are realities of a modern and dynamic supply chain. Whether the hazardous cargo is a final product destined for market or a byproduct of the production process that must be disposed of, hazardous materials transportation remains a necessary part of contemporary commerce.

Traveling with hazardous materials is serious business and maintaining safety is of the utmost importance. To help workers stay safe, the United States Department of Transportation (DOT), established in 1966, and its operating organizations oversee regulations and requirements for the safe transportation of hazardous materials. The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) and the Pipeline Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) work in tandem to advise and enforce regulations in relation to the DOT’s nine classes of hazardous materials.

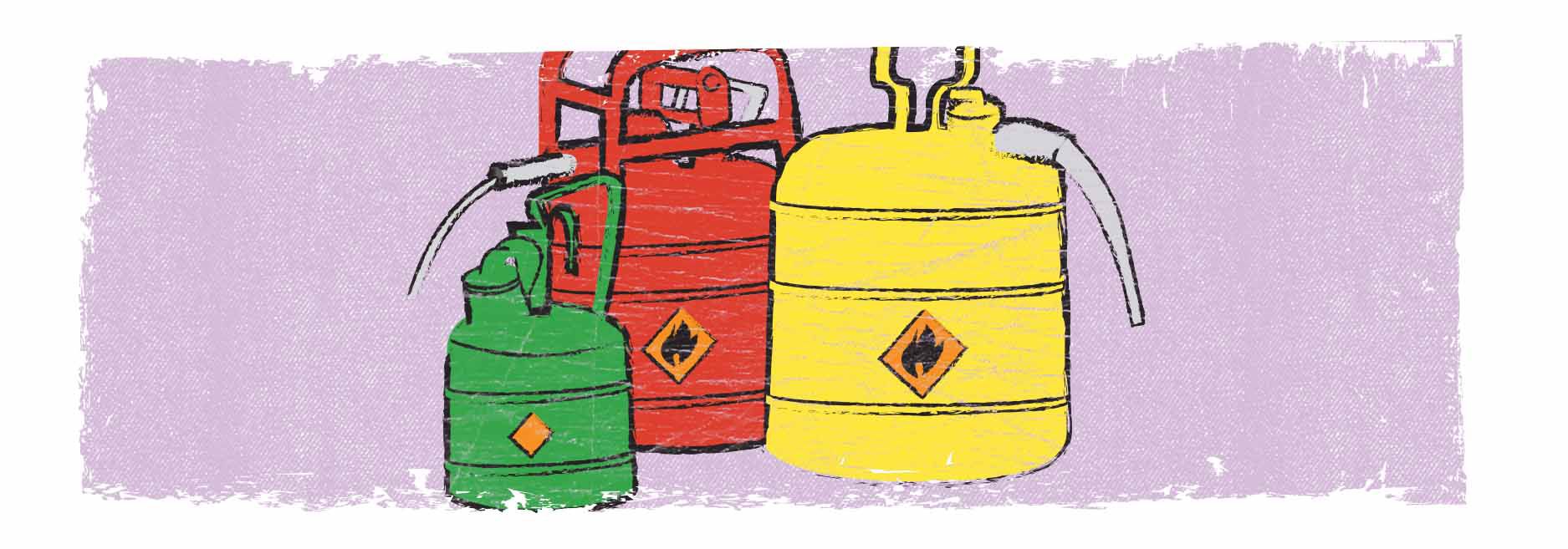

The next stop on our Hazmat on the Go series is Class 3: Flammable and Combustible Liquids.

Examples of flammable or combustible liquids include substances like acetone, ethanol, benzene, biodiesel, crude oil, gasoline and other petroleum products. Since these substances are used as sources of fuel or included as part of the manufacturing processes, they are frequently transported by road and rail and are subject to detailed regulations by the DOT and FMCSA, along with the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) and other organizations.

Flammable and combustible liquids are classified by OSHA by flash point, the temperature at which a compound gives off enough vapor to ignite in the air, and boiling point, the temperature at which a liquid boils and turns to vapor. The categories are ordered from most to least dangerous:

- Category 1 – flash point below 73.4°F (23°C) and having a boiling point at or below 95°F (35°C)

- Category 2 – flash point below 73.4°F (23°C) and having a boiling point above 95°F (35°C)

- Category 3 – flash point at or above 73.4°F (23°C) and at or below 140°F (60°C)

- Category 4 – flash point above 140°F (60°C) and at or below 199.4°F (93°C)

- Any flammable liquid with a flash point greater than 199.4°F (93°C) that has been heated for use to within 30°F (16.7°C) of its flash point is to be handled in accordance with the requirements for a Category 4 flammable liquid.

In conjunction with OSHA’s classification system for flammable and combustible liquids, the DOT and FMCSA classify flammable and combustible liquids by using flash point data. Substances whose flash point is not more than 141°F are classified as flammable liquids, which includes all substances under OSHA flammable liquid categories 1, 2 and 3. Liquids whose flash point is greater than 141°F but less than 200°F are classified as combustible liquids.

When considering flammable and combustible liquids, it is important to remember that the vapor of the liquid is flammable, not the liquid itself. Therefore, flash point benchmarks are used for the classification of flammable liquids because they serve as a direct representation of a liquid’s ability to generate vapor and cause a fire hazard. When vapors of a flammable liquid are mixed with air in the proper proportions, this is known as the flammable range, which can cause a rapid combustion or an explosion if ignited. Since most vapors are heavier than air, they will spread along the ground and collect in low or confined areas.

Due to the level of danger presented by flammable or combustible liquids, special care must be taken in handling an emergency response. During fire hazard events, it’s recommended that emergency responders wear positive pressure self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) and other PPE that helps prevent toxic effects of vapors if inhaled or absorbed through skin. Fire will often produce irritating, corrosive and/or toxic gases, and vapors may cause dizziness or asphyxiation. Depending on the vapor fueling the fire, different firefighting methods should be used, including dry chemical, CO2, water spray and/or regular foam.

As with all nine classes of hazardous materials categorized by the DOT and FMCSA, flammable and combustible liquids must be placarded correctly during transportation and all handling requirements must be adhered to. Flammable and combustible liquids often have strict storage regulations regarding container size, quantity, location and other elements, along with transfer requirements including guidelines for grounding, bonding, piping, ventilation and more.

In 2006, at a chemical mixing area of a manufacturing facility in Illinois, an operator was mixing and heating flammable liquids that included heptane and mineral spirits in an open-top, 2,200-gallon tank equipped with steam coils. A dense fog began to accumulate on the floor below the tank as an ingredient was added. Within about ten minutes, the operation was shut down and most workers had evacuated the area. Unfortunately, the vapor cloud was ignited, causing one death and two injuries. The pressure of the blast was so forceful, the doors to an adjacent area of the building were blown open.

Whether in the workplace or in transport, flammable and combustible liquids are highly volatile and require absolute diligence when handling.

Knowledge of transportation regulations and best practices for hazardous materials is paramount to keeping people safe, on and off the road. Through diligent adherence to safety standards and awareness of emergency response procedures, hazmat transporters can help keep roads safe for everyone.

To learn more about how to protect yourself from different hazardous materials and to find out which DuPont products may offer suitable protection for your needs, visit SafeSPEC™.

Do you have a story you’d like to share about transporting hazardous materials? Email kathryn.novelli@dupont.com to discuss being featured in our next edition of the Glow Worm.

Products and/or sales questions?

Share your stories, tips and tricks.

Resource library

Find technical information, videos, webinars and case studies about DuPont PPE here.