Risky Business: Staying Safe and Avoiding Common Mistakes on the Hazmat Scene

By Grant Coffey

Chief Officer (ret.), Portland, Oregon, Fire & Rescue Hazmat Team

“Wow! We really got lucky on that call! That could have been real ugly…”

Have you heard those words before? If so, take time to consider why your personnel were in the situation to begin with. We all know that our business can be a dangerous one. We weigh risks on a daily basis, but here’s the deal: If you use the words “luck” and “risk” together, you’re fooling yourself.

One definition of a risk is, “A probability or threat of damage, injury, liability or any other negative occurrence that is caused by external or internal vulnerabilities and that may be avoided by presumptive action.” The key words here are “vulnerabilities” and “avoided by presumptive action.” Risks are a given, but how often do you evaluate your vulnerability to them? More importantly, once you’ve identified them, are you taking steps to avoid them?

Dictionary.com defines luck as “the force that seems to operate for good or ill in a person’s life … shaping circumstances, events or opportunities.” In my opinion, luck exists only as an excuse. There are no “lucky” or “unlucky” people, only occurrences and interactions. The intersection of these two is the outcome, and either we’re ready for it or we’re not. We must know our personnel, their preparedness and their abilities, along with the potential risks.

Before examining response changes for implementation, consider this acronym as a safety foundation:

SAFETY (Safety Amounts to Focusing Everything Toward You)

At the heart of it, safety begins and ends with individual responsibility. There is a risk chain, but it must begin and end with you. Let’s look at some issues I’ve seen repeatedly over nearly 40 years in this business.

Blameless

Assuming that someone else is responsible for your safety is setting the stage for disaster. It boils down to officer responsibility and leadership. Establish a team culture of safety, at all times, on all scenes.

Back to Basics

Don’t inundate your personnel with excessive hazmat details and procedures. Do focus on making them comfortable with core concepts. Show them, train them, evaluate them and repeat. Inoculate your team with a foundation of street science for the hazards they commonly respond to.

HUBS (huge useless books)

Do you have hazmat standard operating procedures (SOPs)? If so, when was the last time you reviewed them? When you debrief and discover errors, do you correct your hazmat SOPs, or do you continue to violate them? The very worst thing you can do is continually violate a poor SOP. If your personnel are doing this, find out why and correct or eliminate the issue promptly!

Cues and Clues

With the pressure of an overwhelming hazmat incident, focus can narrow and critical clues can be missed. The key is to unravel the puzzle but also to ask: What am I missing? Field guides can help you improve situational awareness, minimize command overload and catch critical cues and clues

Incident Confusion System

Hazmat and most potential terrorism scenes require multiple agencies to work together. Different agency cultures may equal different understanding and application of the Incident Command System (ICS). Get to know these issues before the incident, not during it. Create an ICS structure before becoming overwhelmed. Conduct cross-agency ICS training. Finally, conduct frequent face-to-face briefings on scene.

Zone Defense

Set early hazardous perimeters based on the threat potential. Many responders position themselves too close upon arrival. This is especially critical for downwind vapor plumes and explosion scenes. Set, communicate and enforce hazard zones. Pay particular attention on explosion scenes. Always suspect a secondary device.

PPExcuses

Require proper proper personal protective equipment (PPE) and enforce its use. Lack of early, full respiratory protection is common on some hazmat scenes and a particular concern during post-fire overhaul scenes. There is no excuse for any significant exposures during the overhaul period. This is a symptom of lack of discipline and leadership; nothing more, nothing less.

Observe Six for Safety:

- Full respiratory protection

- Cooling

- Ventilation

- Time

- Monitoring

- Deacon

Calling the Cavalry

A late call for help is a big mistake because of the response delay. Ask yourself: What three agencies do you respond with the most and how many times have you trained with them in the past year? Develop a relationship with them well before any event. Meet with them; drill with them; learn about their gear and capabilities. And don’t forget to call your hazmat tech team, if needed, for a consult while on scene.

Got Decon?

Poor warm-zone management is also a concern. A common problem is late development of the warm-zone boundary and failure to decon personnel before returning to quarters. Always ID the product and implement an appropriate decon strategy. Removing

Seal the Deal

Many hazmat calls are handled by operational-level first responders. These units occasionally leave the scene without completing required hazmat duties. Your personnel must make proper notifications about any spills, arrange for cleanup and ensure that proper paperwork is filed. Your hazmat techs should deliver a training block for the steps needed to close the loop at any hazmat scene. Give your crews a quick guide for use on scene and always be available for a telephone consult regarding these issues

Grant Coffey retired in 2012 as Chief Officer of the Portland, Oregon, Fire & Rescue Hazmat Program after 37 years of service. He is a hazmat specialist; college fire science instructor; safety officer and radiation specialist; author; and hazmat subject matter expert. Since his retirement, Coffey has been traveling the world, teaching and consulting on hazmat and terrorism issues. If you are interested in free hazmat field guides for any of these issues, please contact Grant at hazmatguy@live.com

The Basic Level A Suits

By Marie Carney

Corporate Safety Representative, DiVal Safety Equipment, Inc.

Imagine, if you will, a petite college intern performing her dream job: collecting water samples from a landfill. It was springtime in western New York and we were pulling samples to test for dense non-aqueous phase liquids. It was cold, gray and blustery, with no end in sight to the weather-induced misery. The ground was thick with snow, so we’d covered the work area with a blue plastic tarp to create a cleared working surface.

As more people tracked across the tarp, the frozen precipitation became slick. Once, as I returned to the work area, I slipped on the tarp and dropped the sample from my hand. I tried to not fall on the test tube, which of course I did, compromising my suit. The next rush of time found the crew using shop rags and garbage bags to clean the area, while I tried to remain calm and cover the breach with my gloved hand. Coworkers led me to an area where I could remove the suit. Fortunately, I wasn’t working with anything acutely hazardous, but the training I’d received prior to donning my Level A suit was invaluable all the same.

Level A suits are fully encapsulating to keep out gas, vapor and particulates, and provide the highest level of protection against direct and airborne chemical contact. In dangerous atmospheres, they can be considered a complete life-support system. Typically worn with a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) enclosed within the suit, Level A suits are usually limited to just 15–20 minutes of use because of their mobile air supply. Because Level A suits contain a respirator, users must be medically cleared prior to donning them.

The Level A hazmat gear includes protective gloves, steel-toe boots and a complete face mask and hood. A positive pressure system inflates the suit slightly to prevent even the slightest gas, liquid or particulate matter from entering the suit and contacting the wearer’s skin. An emergency backup air supply and an intrinsically safe two-way radio may also be worn inside the suit, often incorporating voice-operated microphones and an earpiece speaker for monitoring the wearer and the site conditions. There may also be a water supply and drinking tube included for longer job functions, especially in warm environments.

All of the protective aspects of a Level A suit are great, but they do make it quite heavy, which can exhaust even the strongest worker. Wearers must take slow, steady steps and carry their equipment carefully to avoid puncturing or ripping the suit during operations.

No matter what level of PPE workers need for a job site or task, it’s always important to train them to check for defects or visible malfunctions prior to use. There are two different recommendations for testing Level A suits. In the first, the user is required to perform nine separate exercises while wearing their suit, which indicate how the suit would perform in actual field operations. In the second test, the suit is connected to a Universal Pressure Test Kit and fully inflated. Depending on the space you’re working in, you may opt to send the suit out to a competent person for testing as it can take up a bit of space, and in cramped quarters you might put a hole in the suit while testing it.

Level A suits can be used in many applications, and they’re a very important form of PPE for environmental, medical and chemical workers. Wearers should always be aware of and trained on the hazards they might face on any jobsite where the potential for exposure exists. Make sure you consult with the Safety Representative and read their job safety analysis (JSA). Understand, too, that if the PPE fails you need to remain calm and remember your training!

For more information on Level A suit testing, visit the following resources:

ASTM F1154-11, Standard Practices for Qualitatively Evaluating the Comfort, Fit, Function, and Durability of Protective Ensembles and Ensemble Components, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2011, www.astm.org

ASTM F1052-14, Standard Test Method for Pressure Testing Vapor Protective Suits, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2014, www.astm.org

For more information on which DuPont Level A suits might apply to your level of hazardous materials work, visit http://safespec.dupont.com

Making Sense of Hazardous Materials Response Standards

By Rick Edinger

Chairman, NFPA Hazardous Materials Response Committee

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) maintains a number of standards and recommended practices related to hazardous materials response. Standards associated with protective clothing include NFPA 1991, 1992 and 1994. Documents that guide response to hazardous materials (hazmat) incidents include NFPA 472, 473, 475 and 1072.

The NFPA Hazardous Materials Response Committee has done significant work in the past five years, including developing two new documents (475 and 1072) and updating two legacy standards (472 and 473). NFPA 472 and 473 are minimum performance standards that provide specifications for training emergency responders to various competency levels. NFPA 473 addresses emergency medical services (EMS) preparation and response to hazmat incidents.

Developed with public input, NFPA 475 is a “soup to nuts,” how-to document that is a great reference for anyone leading hazmat response teams. It is a recommended practice, i.e., it contains “should” versus “shall” language. From risk assessment to personnel management to finances, NFPA 475 provides readers with a compendium of information on hazmat response programs.

NFPA 1072 was developed as a companion to NFPA 472. While NFPA 472 is written in competency-based language, NFPA 1072 is written in a job performance requirements (JPR) format. Readers should think of NFPA 472 as the “parent” document and NFPA 1072 as the “child.” If you need hazmat response competencies, NFPA 472 is the go-to standard. If you’re looking for JPR equivalences, NFPA 1072 is your guide.

The NFPA also publishes a Hazmat Handbook that follows revisions to NFPA 472 and provides readers with expanded language related to the specific competencies contained in the 472 document.

The NFPA Hazardous Materials Response Committee is made up of a cross-section of hazmat responders, industrial response personnel, training officials and other subject matter experts who bring their expertise to the effort of maintaining these documents. NFPA standards and recommended practices are consensus documents that follow a very specific process for receiving input, making changes and publishing revisions.

The committee relies on public input to guide revisions and share their needs and ideas for keeping these documents relevant. The public input process for all four documents is now open. Those interested in viewing the documents and providing input can gain access through the NFPA website. Simply type in the document name or number in the search box and you’ll gain access to information about all aspects of these standards.

Hazmat Through History: Anthrax

By Daniel Hammel

Marketing Consultant, DuPont Personal Protection

Anthrax is a bacterial disease affecting livestock and humans. Ancient in origin, it was first clinically described in the 18th century. The name anthrax derives from the Greek word for coal, as black lesions are a symptom of cutaneous anthrax. Skin infections are by far the most common form of anthrax, but have a relatively low risk of death.

Respiratory anthrax infections, while much rarer, have a historic mortality rate of 85%, even when medically treated. Inhalational anthrax has a higher mortality rate in part because initial symptoms are often confused with those of colds or the flu. If treated before the second stage, the mortality rate of inhalational anthrax drops to 45%.

A usual means of anthrax infection is from consuming or handling infected animals, including their wool and hides. Inhalational anthrax was once known as “wool-sorter’s disease” because of this risk. Infections can also be intentional, and terrorists have used powdered anthrax spores as a biological weapon.

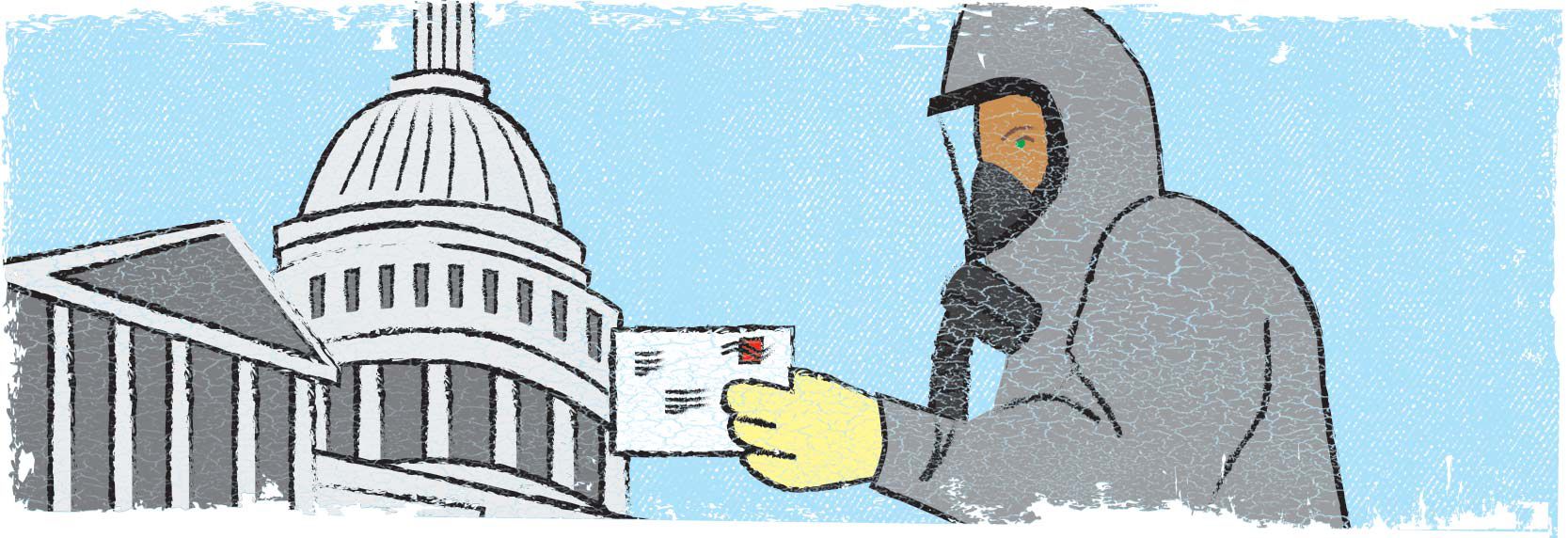

In 2001, letters with powdered anthrax spores were mailed to media outlets and two U.S. senators. Beginning one week after the September 11 attacks, the letters continued to be sent for several weeks. Tragically, five people died and 17 more were infected. The key suspect committed suicide prior to being brought up on charges. Dozens of buildings needed to be cleaned and decontaminated in the aftermath.

Today, workers in both governmental and private mailrooms wear protective apparel to help prevent anthrax exposure, and controls have been implemented to help detect or capture anthrax spores.

To find out which DuPont products offer suitable protection against hazardous particles, including anthrax, visit www.SafeSPEC.DuPont.com.

Join the DuPont™ Tychem® Trainer Advantage Program

By Cindy Bowen

TTAP Manager, DuPont Personal Protection

Looking for a way to keep your hazmat training program up to date? The DuPont™ Tychem® Trainer Advantage Program (TTAP) provides support for first responder training facilities across the United States. TTAP offers excellent equipment, technical support and some of the most advanced materials available to enhance the training experience. We believe that how you train isn't just important, it's critical. To find out more about program requirements and the benefits of becoming part of the TTAP community, please contact Cynthia.Rives.Bowen@dupont.com.

Products and/or sales questions?

Share your stories, tips and tricks.

Resource library

Find technical information, videos, webinars and case studies about DuPont PPE here.